Learn about efforts to conserve this rare nocturnal primate.

About the Loris Project |

Helena´s

other websites:

To the personal website and publication list To the husbandry manual for Asian Lorisines (H. Fitch-Snyder, H. Schulze, eds., 2001) To the loris and potto conservation database |

| About the Loris Project

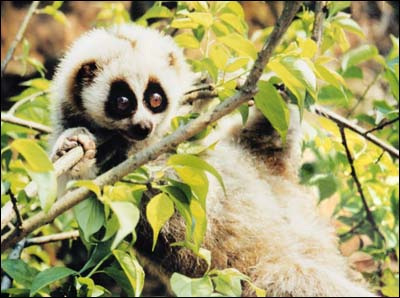

Lorises are specialized, nocturnal primates from Asia. Very little is known about them in the wild. Three kinds of loris reside at the Center for Reproduction of Endangered Species (CRES) loris facility, where scientists have been conducting a wide range of studies on their behavior, biology, reproduction, and genetics. Of the three currently recognized loris species, two of them, the slow loris (Nycticebus coucang) and the pygmy loris (Nycticebus pygmaeus), are found in Vietnam. Lorises are especially challenging to study in the wild because they live in dense forests, and are only active at night. Until very recently, it has not been possible to conduct nocturnal surveys in the Vietnamese forests. Thanks in part to the persistence of Professor Vu Ngoc Thanh from Hanoi University, and the support of wildlife officials at Ben En National Park, we were able to perform a loris survey in northern Vietnam. We have also initiated research, education, and conservation programs for these primates. |

|

|

Our Adventure Begins

It took several long days to reach our research site. From Hanoi, we drove all day to get to Ben En National Park. It is only about 124 miles (200 kilometers) south of Hanoi, but the roads were rough (especially by jeep). We also had to stop in every province, district, and commune to obtain permits, and meet with government and forestry officials. We spent the first night at the park headquarters, and the director informed me that I was the first westerner to ever visit that reserve. Ben En Park contains over 41,000 acres (16,634 total hectares), and about 14 percent of the park consists of an artificial lake with many islands and peninsulas. The local villagers living in the areas we visited were of Thai and Tho nationalities, both of which subsist on rice farming. We traveled by motorboat to a site further into the forest, and spent

the following night at a forestry station. After dark, we rode in a shallow

"bamboo basket" boat to a nearby island, but we weren't able to find any

lorises. We used the same boats the following day to travel to a larger,

more distant island. After hiking for several hours, we found an old abandoned

forestry station where we set up our tents. This site was located in a

secondary forest with mixed bamboo and hardwood trees.

|

|

|

|

in the area near Ben En National Park. |

Shallow "bamboo basket" boats took researchers to nearby islands. |

| My First Loris Sighting

February 22, 2001 I can hardly believe that after 30 years of studying these animals, I finally saw my first loris in the wild! Since we didn't find any lorises on the first two trails we explored, we chose three new trails the next night. This area of the forest was thick with tall grasses, bamboo, and endemic hardwood trees. The trails were very narrow, and many of the branches hung down so low that we had to stoop as we walked. After several long hours, I was beginning to wonder if there really were any primates left in this forest at all. We had seen no evidence of any of the eight primate species that were reported to live in this reserve. Reports from the local people weren't encouraging about the presence of other primates, but they did confirm that lorises had recently been seen in this area of the forest. Suddenly, my headlamp caught the unmistakable reddish-orange eye shine of a loris on top of a tall tree. I immediately alerted my assistants, and they both began to climb the tree to try to catch it. We were hoping to get a closer view of the loris so that we could determine the sex, estimate its age, and take some photographs. |

|

After we spent nearly 30 minutes pursuing the loris, it finally moved out of view, and our team headed back to camp to report our find to the rest of the crew. Everyone congratulated me for being the first person to find a loris, and we had a hearty celebration. After all the years of work that led up to this event, it was extremely rewarding to finally see a real live loris in the Vietnamese forest!

| Other Loris Sightings

March 2, 2001 We traveled through the forest to our next site by jeep. Many of the roads were little more than footpaths and water buffalo trails that were made additionally challenging because of the muddy conditions and thick overgrowth. Therefore, we had to rely on the assistance of several local villagers to help widen the road so that we could reach our destination. For most of the way, we walked ahead on the trail and waited for the jeep to catch up with us. The local children were very curious because they had never seen a Westerner before, and a large group followed us as we walked along the road. When we reached the second field site, we stayed with a local Thai family in their bamboo house. This spot was further away from the lake than the first place we surveyed, and the villagers' homes had a spectacular view of the nearby mountains. We found a variety of interesting animals in this location. Some of the frogs were particularly fascinating, including a giant green tree frog that was larger than a man's hand. Two animals that our local guides were not pleased to encounter were a green bamboo viper snake and a scops owl. Owls are believed to bring bad luck, and for that matter, so are lorises! It is amazing that we were able to convince our guides to do the night surveys at all. All of our efforts finally paid off on our third night at this site. The weather had become very damp and misty, and the heavy drizzle reduced the effectiveness of our headlamps. Our team decided to split up into four groups so that we could cover more territory. We were thrilled to find seven pygmy lorises that night, and we even managed to catch one! The one we caught turned out to be a handsome young male, and Professor Thanh brought him back to camp in his backpack. The following day, we took photographs, measurements, hair samples (for genetic analysis), and fecal samples (for diet and parasite analysis). This loris happened to have a heavy load of pinworm parasites, but otherwise, he looked very healthy. We released him into the forest after we finished collecting data. |

|

|

|

| Curious local children had never seen

a Westerner before. |

This giant green tree frog is larger

than a man's hand. |

Benefits of Bamboo

March 4, 2001

I am fascinated at the seemingly endless uses for bamboo. Besides building their homes, boats, and fences out of it, the villagers even use the pulp to make paper. My Vietnamese research team used bamboo tubes to design carrying cases for the batteries that were attached to their headlamps. They also carved tobacco pipes and musical instruments from bamboo. Many of these items were left behind as we walked through the forest. Several types of bamboo are abundant in this forest, and it only takes a few minutes for our local guides to fashion a new pipe or flute with a few hacks of their sharp knives.

I was able to fully appreciate the value of this plant after I experienced

a memorable event in the forest. Usually our team ate our meals in camp,

so I was surprised when one of my assistants showed me some dried noodles

that he was carrying, and told me that we were going to cook them in the

forest that afternoon. Where was our pot to boil the water? How would we

eat the noodles without bowls or eating utensils? When we arrived at our

resting spot, our local guide quickly went to work building a fire by a

stream, and cutting thick green stocks of bamboo that grew nearby. He filled

a large tube with water from the stream, and packed the top end with leaves

to form a lid. He placed this cooking utensil directly over the fire, and

held it upright with a bamboo frame. The fire was so hot that the outside

of the tube sizzled and turned black, but it still held up to the tremendous

heat. While waiting for the water to boil, my assistants formed large bamboo

stalks into bowls, and carved chopsticks for each of us. When the water

was boiling, we placed our dried noodles into the bowls, and poured in

the water. In a few minutes, our meal was ready to eat. The noodles had

a wonderfully delicious flavor that came from the green bamboo cooking

vessels.

I am very impressed with the way that our local guides were so knowledgeable

about the wealth of resources in their forest environment. They are able

to identify food, medicine, or tool uses for nearly everything in the forest.

|

|

|

| Helena learned that thick bamboo

can be used like a pot to boil water for noodles. |

Even chopsticks can be fashioned

out of bamboo. |

Villagers find endless uses

for versatile bamboo. |

Even though the forest and wildlife are legally protected, the laws

are difficult to enforce. The forest rangers do not have the time or resources

to patrol most areas of the reserve. One added benefit of doing this loris

survey is that it provided a rare opportunity for rangers to travel to

some of the more remote areas of the park. Unfortunately, we found clear

evidence of wood poaching in both of our main survey areas.

It is very time-consuming for the local people to poach the large,

endemic hardwood trees. After the trees are felled, each tree must be cut

into manageable pieces using handsaws and other primitive tools. The poachers

then transport the wood out of the forest via water buffalo or bicycle.

Along the trails, we found at least five fallen trees that were being prepared

for transport. The rangers also caught two groups of poachers carrying

wood out of the forest. Rangers usually fine the poachers and confiscate

their tools. In some cases, the rangers may also confiscate the poachers'

water buffalo and bicycles.

Although I was glad to see the forest was being protected, I had mixed

feelings about the poachers who were just trying to provide for their families.

These people, like their ancestors, lived in these areas long before Ben

En became a national forest. One of the biggest challenges of habitat protection

is balancing the needs of the people with those of the environment. I hope

that we will be able to develop conservation programs that benefit everyone.

|

|

| Taking wood from the protected forest is,

unfortunately, a common occurrence. Photos taken by Vu Ngoc Thanh |

Rangers can confiscate a poacher's

bike or water buffalo. |

I am encouraged that we are developing collaborative conservation programs

for lorises and other species. It is especially important for us to pursue

these efforts now, while lorises are still present, rather than waiting

until there are only a few remaining in the wild.

|

|

| A confiscated loris is released

in an island reserve set up for these rare primates. |

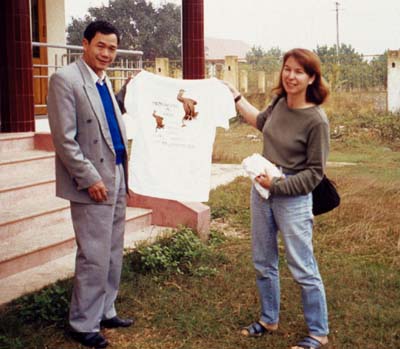

We can encourage loris conservation

by distributing t-shirts, posters, and other educational materials. |

Figures and text: copyright San Diego Zoological Society, with permission